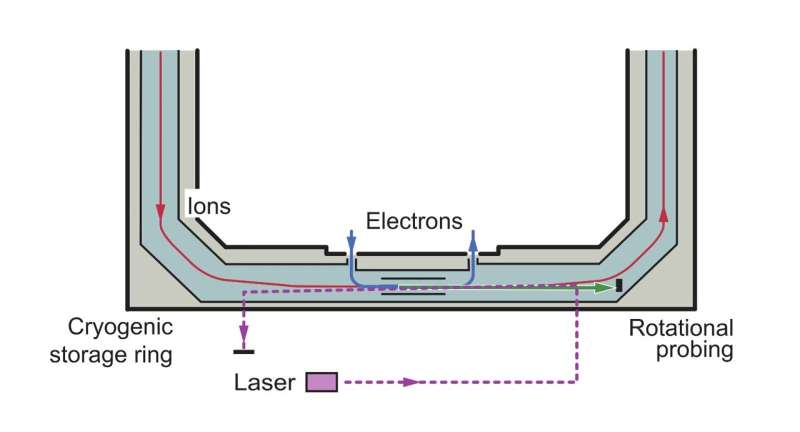

A simplified schematic diagram of an experiment showing the relevant parts of a cryogenic storage ring (CSR). The red and blue trajectories emphasize the ion and electron beams, respectively. The accumulated ions can interact with the combined electron beam or pulsed laser beam (dashed purple). The laser interaction product is neutral and continues ballistically until it is collected by the particle counting detector (green arrow). Credit: Kalosietal.

When freed in cold climates, molecules slow down and spontaneously cool by losing rotational energy in quantum transitions. Physicists have shown that this rotational cooling process can accelerate, decelerate, and even reverse by colliding with surrounding particles.

Researchers at the Maxplank Institute for Nuclear Physics and the Columbia Institute for Astrophysics in Germany recently conducted experiments aimed at measuring the velocities of quantum transitions caused by collisions between molecules and electrons. Their findings are Physical Review LetterProvides the first experimental evidence of this rate, previously estimated only theoretically.

“If electrons and molecular ions are present in a dilute ionized gas, the collision process can change the lowest quantum-level population of molecules,” said Abel Karoshi, one of the researchers who conducted the study. I told org. “An example of this process is the interstellar cloud, where observations reveal primarily the lowest quantum state molecules. The attractive force between negatively charged electrons and positively charged molecular ions makes the electron collision process particularly. It will be efficient. “

Physicists have long sought to theoretically determine the strength with which free electrons interact with molecules during collisions and ultimately change the state of rotation of the molecule. But so far, those theoretical predictions have not been tested in experimental settings.

“Until now, it was not possible to measure the effectiveness of changes in rotational levels for a given electron density and temperature,” explained Kálosi.

To collect this measurement, Kálosi and his colleagues brought the isolated charged molecule into close contact with the electron at a temperature of about 25 Kelvin. This allowed them to experimentally test the theoretical hypotheses and predictions outlined in previous studies.

In their experiments, researchers used a cryogenic storage ring from the Max-Planck Institute for Nuclear Physics in Heidelberg, Germany, designed for species-selected molecular ion beams. In this ring, the molecules move in orbit like a racetrack in a cryogenic volume. This orbit is very highly empty from other background gases.

“In cryogenic rings, the accumulated ions are radiated toward the temperature of the wall of the ring, producing the ions produced at the lowest number of quantum levels,” Kálosi explained. “Recently, some cryogenic storage rings have been built in some countries, but ours is the only facility with a specially designed electron beam that can be manipulated to contact molecular ions. Ions are stored for minutes. This ring uses a laser to study the rotational energy of molecular ions. “

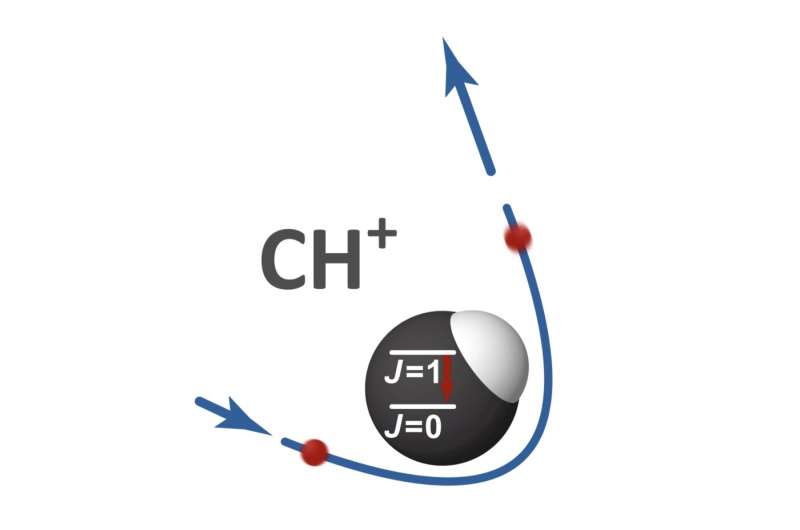

The artist’s impression of a rotating state that changes the collision between the molecular target (CH +) and the electron. The rotational quantum states of molecules labeled with J are quantized and separated by well-determined energy steps. Only when the collision energy of the particles exceeds this threshold can the collision increase the quantum number J. Otherwise, as in the experiment, a net decrease in J, which is the rotational cooling effect of the collision, is observed. Credit: Kalosietal.

By selecting a specific light wavelength for the probe laser, the team can destroy a small portion of the stored ions if the rotational energy level matches this wavelength. Next, we detected a fragment of the broken molecule and obtained a so-called spectroscopic signal.

The team collected measurements both in the presence and absence of electron collisions. This allowed them to detect changes in levels of the population under the cryogenic conditions set in the experiment.

“To measure the process of collisions with changing rotational states, we need to ensure that only the lowest rotational energy levels are incorporated into the molecular ions,” says Kálosi. “Therefore, in laboratory experiments, it is necessary to use cryogenic cooling to temperatures well below room temperature, which is usually close to 300 Kelvin, to keep the molecular ions in a very cold volume. In this volume, the molecules are kept. It can be separated from the ubiquitous ., Infrared heat radiation of our environment. “

In their experiments, Kálosi and his colleagues were able to achieve experimental conditions in which electron collisions dominate the radiation transition. By using a sufficient number of electrons, it is possible to collect quantitative measurements of electron collisions with CH.+ Molecular ion.

“We have found a velocity of electron-induced rotational transitions that is compatible with previous theoretical predictions,” Kálosi said. “Our measurements provided the first experimental test of existing theoretical predictions. Future calculations are even more resistant to the potential effects of electron collisions on the lowest energy level populations of cold and isolated quantum systems. I hope to focus on it. “

In addition to confirming theoretical predictions in the experimental environment for the first time, recent research by this team of researchers may have important research implications. For example, their finding is that measuring electron-induced quantum-level rate of change is when analyzing the weak signals of cosmic molecules detected by radio telescopes and the chemical reactivity of dilute and cold plasmas. Suggests that it may be important to.

In the future, this paper may pave the way for new theoretical studies that more closely examine the effects of electron impacts on the occupancy of the rotational quantum level of cold molecules. This can help identify the cases where electronic impacts have the strongest impact, which can lead to more detailed experiments in this area.

“Crystal storage rings will introduce more versatile laser technology to study the rotational energy levels of more diatomic and polyatomic molecular species,” Kálosi added. “This paves the way for electron impact research with a wide range of additional molecular ions. This type of laboratory measurement uses a powerful astronomical table such as the Atakama large millimeter-wave / submillimeter-wave array in Chile. And especially continue to complement observational astronomy. ”

Collisions with electrons cool molecular ions

Ábel Kálosietal, laser probing of rotational cooling of molecular ions by electron impact, Physical Review Letter (2022). DOI: 10.1103 / PhysRevLett.128.183402

© 2022 Science X Network

Quote: Laser technology is used to measure the rotational cooling of molecular ions that collide with electrons (June 1, 2022). Obtained June 1, 2022 from https: //phys.org/news/2022-06-laser-technology-rotational-cooling-molecule. html

This document is subject to copyright. No part may be reproduced without written permission, except for fair transactions for personal investigation or research purposes. Content is provided for informational purposes only.

Commentaires

Enregistrer un commentaire